Remembering Ramsey Lewis (1935-2022)

“Life is good.” Always said with a smile that I could clearly hear and feel over the phone, this was Ramsey Lewis’ motto - the line he said nearly every time I asked him how he was doing. He often repeated it twice, the second time with even more enthusiasm: “Life is good. Life is GOOD!” And life for Ramsey sure was good. As he often told me during these past few years, “I’m at the ‘do what I want when I want to do it and if I don’t want to do it I don’t do it’ phase of my life.” Life was so good, in fact, that he often told me to “take care of yourself so that one day you can enjoy life at 87 as much as I do. The air is good up here.” One time he added, “Wait until you’re 87,” to which I replied, “I’ll wait,” which cracked him up.

Ramsey has always been one of my biggest piano heroes. I’ll never forget the day I got my driver’s license. I drove around all afternoon by myself listening to “The In Crowd” with the windows down. Man, I felt cool!

In getting to know Ramsey over this past decade, he’s become one of my biggest life heroes too. I’ll never forget the first time I began to get a feeling for the gentleman behind his iconic piano playing. It was the first time we met, at the 2010 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Awards where I was working as a student volunteer. That morning, I was tasked with greeting the Jazz masters as they arrived for brunch. Within a fifteen minute period, I welcomed legends including Dr. Billy Taylor (who postponed greeting his old friends to ask me what I’ve been practicing), Jimmy Heath (who asked where the restroom was. “Time to see Mr. Pickle,” he said.), Gerald Wilson (who, after shaking my hand asked me to “please, pardon my glove.”), Nat Hentoff (who told me he felt like he was at a family reunion), Yusef Lateef, James Moody, and so many others. As each master got off the elevator, I’d introduce myself, point them in the direction of the brunch and tell them that if they needed anything to please let me know. While everyone was kind and gracious, no one, except for one person, introduced themselves back to me after I introduced myself.

“Hi, I’m Joe,” I said as Ramsey Lewis stepped out of the elevator.

He approached me with a big smile on his face, his hand out to shake mine, and in his slow, cool-tempered voice said, “Nice to meet you Joe. I’m Ramsey Lewis.”

Just like everyone being honored that day, he must’ve known that all of us student volunteers knew who he was, but he went that extra mile, and I left that day with a greater appreciation for Ramsey Lewis, the person.

Three years later, I was incredibly fortunate to have my first opportunity to open for him, at New York’s Blue Note. At the end of my set, Ramsey’s manager approached me and told me that he wanted to see me in his dressing room. Oh shit! Anxiously awaiting to hear how badly I’d messed things up, I nervously entered his dressing room - and thankfully, how wrong I was! The first words out of Ramsey’s mouth were, “I’m sure glad I got here early tonight to hear you. You can really play.”

I told him that his influence had a lot to do with that, but he shooed it off. “No man,” he said. “You’ve got your whole own shit together. Keep at it!” He then handed me a piece of paper with his email address on it. “Email me,” he said. “Tell me what you're up to. And I will write you back.”

I did just that, and so did he. I sent him a thank-you note a few days later, and inspired by hearing him talk on stage that night about his love of Nat “King” Cole ballads, I attached a recording of me playing the ballad, “I Guess I’ll Have To Dream The Rest.”

He responded soon thereafter, with “Ah hah! How beautiful. You are a romanticist too.” One of the many things the two of us bonded over over the years is how, while we love to swing and get funky (although Ramsey didn’t like the word “funk” - to him, it implied gimmicky riffs), what we both really love playing are romantic ballads.

One month later, after the sustain pedal of a piano broke midway through one of my performances, I reached back out to Ramsey (who I then addressed as Mr. Lewis), to see how, if possible, I could be prepared for such a disaster. A few days later my phone rang. I didn't have his number yet and in a rush to class didn’t answer. I checked my voicemail after class. A voice just began talking: “So I’m playing at the Banbarks in Denver, Colorado. It’s a little nightclub. And I’m showing off, and we’re playing so hot - a trio in those days -, and we’re getting to the end of the tune, and there’s to be a big glissando from the top of the piano down to the bottom of the piano and then a big chord. I started to glissando from the top of the piano, and as I got down to the bottom of the piano I slid off the bench on the floor, under the piano. That was the big finish. No doubt we got a big applause. I don’t know if it was from the glissando or from me falling on the floor. Joe, it’s Ramsey Lewis. Sorry I missed you. I will call again. Just bear with whatever it is, man. Go with the flow. You know how these pianos are. When you get to a certain level you can demand a certain piano and those kinds of mishaps won’t happen, but nothing’s 100 percent. I wish you all the best. Talk to you soon.” And that was the start of a beautiful friendship.

I’d mail him interesting books and albums, and he’d share the same with me. I remember him calling once after I mailed him a Luckey Roberts album. He was touched by the gesture. “You are the best”, he said in his voicemail thanking me. And then, through noticeable tears, “You’re one of a…one of a…very special guy…one of a kind.”

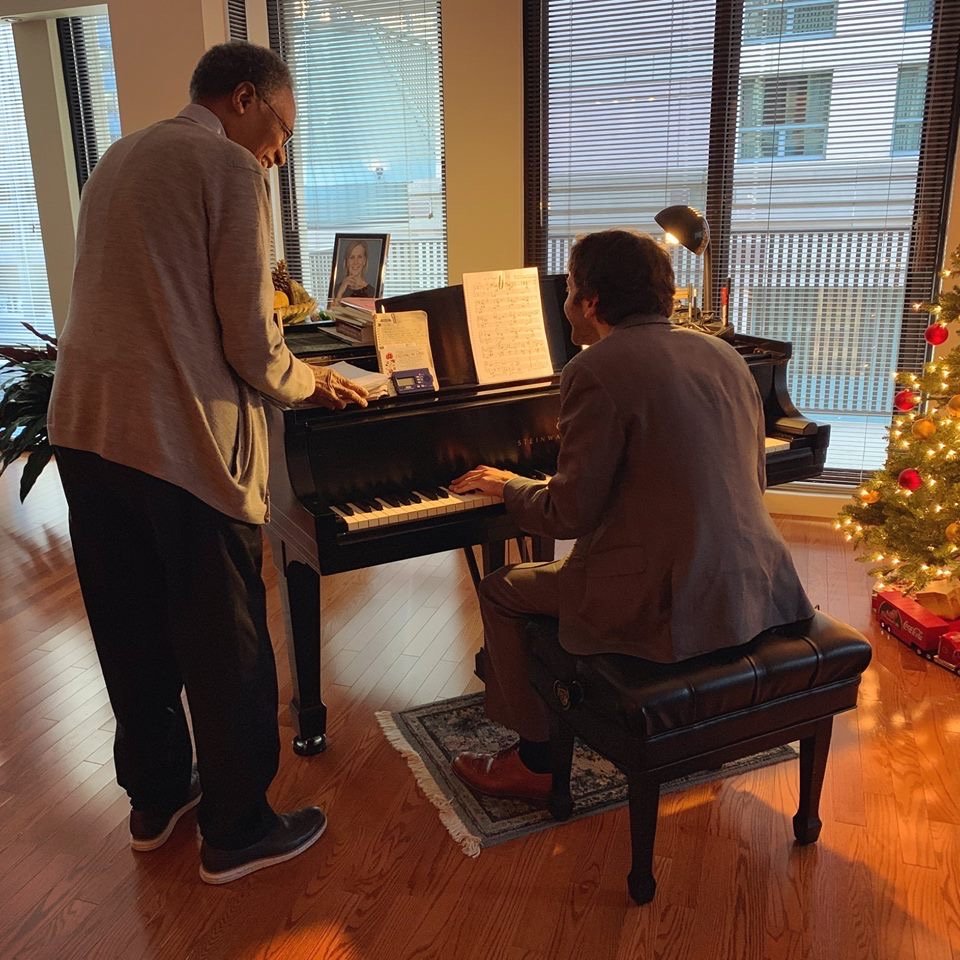

I opened for him a few more times over the next three years. One night, he enthusiastically met with my whole family, praising me to my parents, which meant a lot. I found it amazing that my Dad had introduced me to Ramsey’s music, yet here I was years later introducing my Dad to Ramsey. Ramsey was touched by my eventually telling him that, adding that he had had a similar experience with his father and Count Basie.

I’d often sit with him in his dressing room during his set breaks, where he’d tell me stories about Oscar Peterson, Count Basie, Buddy Rich, Billy Taylor and more. He was an open book, always ready to talk about whatever was on my mind.

While I learned something from nearly everything he shared with me, I never once felt like he was talking down to me. He made me feel very comfortable talking to him, almost like it was just two Oscar Peterson fans on the phone together. The then 78 year-old Ramsey Lewis reminded me of every 18 year-old college Jazz student I’d met at NYU who had just moved to New York and was excited about studying, learning and listening to this music. He always made me feel apart of the club. Not just the Blue Note, but Ramsey’s club, or the In Crowd, as some would say. Once, he introduced me to a friend of his in the dressing room: “Joe’s a fantastic piano player who plays his butt off”, he said. Then he got excited and began to talk louder and faster. “He can play everything. I mean everything. Solo, trio, you name it.” I was speechless and said something about how much that meant coming from him. Then he looked at his friend and said, “And he's humble! Which makes it even hipper!”

Once I called and asked his advice about talking to the audience on the microphone. At the time, I felt very uncomfortable on the mic. His response: ”If you were faking it you'd have something to worry about. But you're not faking it. You play the f*** out of the piano. So, when you pick up the mic you need to say to yourself, ‘I’m Joe Alterman and I play the f*** out of the piano, motherf****.’ He told me how Billy Taylor had helped him feel more comfortable on the mic, adding, “I noticed that the more comfortable I seemed, the more comfortable the audience became.”

As our relationship developed and our conversations deepened, I began to see Ramsey not only as a music mentor, but as a life one, too.

Once I called him asking for dating advice. At the time, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to date a musician or not; dating a musician often became too much, and dating a non-musician often became too little. “Joe,” he told me. “You’re not my son but I speak to you like you’re one of them.” As we began to speak with more frequency, I’d hear that quite often. “You’ve got it all wrong. Instead of looking for people who check off your check list, look for someone who simply loves you enough to want to explore and discover the things that are important to you.”

Ramsey composed a piano concerto and performed it with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on his 82nd birthday. Shortly after, I called and asked how it went.

“Joe,” he said. “I’ve got to tell you what happened: I wanted to take piano lessons as a youngster, but I grew up in a very poor family and even though my Dad was a great lover of music, piano lessons cost 50 cents and we couldn’t afford it. Finally, I made so much noise around the house that they relented and got me lessons. I had hopes and dreams of becoming a classical pianist, and very studiously went down that path for many years. I was a teenager, maybe 15, 16 years old when my teacher told me that I had the talent and the skills to be a concert pianist, but that it would never happen for me; there simply weren’t any opportunities for Black people in classical music at the time. That’s when I discovered jazz. Anyway, nearly 60 years later, I’m turning 80 years old and about to debut a piano concerto I wrote with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Me playing with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra? In my Dad’s wildest dreams. Anyway, there’s nearly 18,000 people in the audience. I’m about to walk on stage and the lady backstage says that I can’t go on. ‘Oh no!,’ I thought. ‘Are my dreams shattered?’ “No” she said. “We have a surprise for you.” All the sudden, I look up at a big screen on the stage, and President Obama’s face comes on it. He gives a whole speech about how I’m a national treasure, wishing me a happy birthday. Joe, I couldn’t become a classical pianist because I’m Black. Now, at 80, I’m finally realizing those classical music dreams and the Black President comes on the screen to wish me a happy birthday.” Then, through tears he told me, “I just wish my Dad could’ve been there.”

One of the most powerful stories I’d ever heard, I asked Ramsey if we could turn it into a short story, which we did, and that process brought us even closer.

I began thinking about moving home to Atlanta in early 2016 and was nervous for my career and the regrets I might have leaving New York. While many people told me leaving New York would be devastating for my career, Ramsey’s advice brought me home, literally. “It sounds to me that what you're saying is that you have a lot of people down in Atlanta who make you feel all warm and fuzzy inside. Some people spend their whole lives looking for that, and never find it. And some people don't find it until they're 50. You're lucky to have found it at 27. We only go though this one time. Life's too short. My advice to you: get on that plane tonight! And don't worry about not being in New York. You play your ass off - the word will get out. I hope next time we talk you say 'I'm moving’.”

A few days later, I called him back to tell him that I was moving. However, a few days after that Paul McCartney showed up at one of my gigs - which I took as a sign that I shouldn’t move home, and I shared that feeling with Ramsey, who put things in perspective for me. “Imagine that Paul McCartney comes to every one of your gigs,” he told me. “It wouldn't be so exciting after a while.”

I moved home two months later, but shortly before doing so, I went to hear Ramsey play at an auditorium in Brooklyn with plans to visit with him after the show. However, maybe three minutes before the show was supposed to begin, Ramsey called me. It was a rainy day and he said that because of the weather, he was going to have to head back to Chicago right after the show. However, he wanted to see me, so he asked me to come backstage right then, which I did, and he postponed the concert by ten or so minutes just so that we could spend some time together.

After moving home to Atlanta, we’d have many special phone conversations. Lots of laughs and deep talks about music, politics, life and so much more. Referring to our chats and to his wonderful wife Jan, he once told me, “Sometimes when you and I get off the phone Jan comes in the room and says, ‘You must've been on the phone with an old person.’ I say, ‘Nope, that's little Joe.’”

One time he cracked me up when he called from Las Vegas joking around: “Hey Joe,” he said very quickly. “I just won $4 million dollars at the slots, so I’m going to go get myself some new friends. Sorry, bye!”

I once asked him if he ever got nervous before a concert. “It’s not nerves,” he corrected me. “It’s professional anticipation.” I loved that.

Another thing that really impressed me about him was that he seemed to have a reason for everything he did. He told me, “I’m mindful of where I am, who’s standing next to me, how I feel, at all times. Be mindful of where you are at all times. I’m that way everywhere.”

In regards to practice, he said, “I always practice with a purpose.”

He was always so encouraging about my music, which he often called “happy serious music,” a phrase that I love.

One of the most profound things he ever told me was an off-the-cuff comment: “Music is man’s contribution to nature. Like nature contributes to flowers to help the landscape, man contributes music to help our daily life.”

Ramsey always answered the phone with the same greeting: “Joe Alterman! The people’s choice!” Our conversations always ended with me feeling better than when we began. I’ll miss those.